Cataloguing the DMA’s Rembrandt Prints

This summer I worked as the IFPDA Foundation Summer Intern for Prints and Drawings. During this time, I catalogued the DMA’s Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) print collection, which includes 42 prints. Cataloguing has consisted of taking measurements, updating titles and mediums in TMS, determining a print’s state, and identifying watermarks.

Rembrandt van Rijn was a Dutch artist who is known for his dramatic paintings and innovative etchings, with subject matter varying from biblical stories, self-portraits, landscapes, and more.

Rembrandt primarily printed etchings. The etching process begins with covering a warm metal plate, often copper, with a ground, such as wax. Next, the artist uses a needle to etch in the wax where they want ink to be held. The plate is then submerged in an acid bath, which eats away at the exposed metal. Once the desired depth of line is achieved, the plate is removed. Wax is taken off, ink is rubbed into the lines, excess ink is wiped away, and finally, damp paper is set atop the plate and run through the printing press. Since the artist makes their marks in soft wax, etchings often replicate the free, sketchy effect of paper drawings.

Rembrandt frequently reprinted his prints and would sometimes adjust the copperplates. Each change in a plate marks a new print iteration and is then deemed a new print state. Since Rembrandt’s copperplates continued to circulate after his death, people continued to alter his plates and create posthumous states. However, a print’s state does not necessarily guarantee whether it is lifetime or posthumous. Since a print’s state does not provide certainty about its printing date, researchers study the paper to glean more information.

A paper’s watermark can sometimes determine its origin. Watermarks are symbols found in paper that represent a specific paper mill. To create a watermark, paper makers start with a paper mold made of a wire grid and wooden frame. Then they create a unique wire design and sew it into the mold. The mold would then be submerged in a vat of diluted fibrous pulp. When lifted, water would drain and leave a layer of pulp. Wires from the mold have the thinnest coating of pulp and create thin impressions in the paper. Upon first glance, wire marks are not visible until a light is shone through the paper.

Out of the 42 Rembrandt prints in the DMA’s collection, I identified 12 watermarks. There are around 50 various watermarks plus their variants or subvariants found in Rembrandt’s prints that are catalogued in Erik Hinterding’s Rembrandt as an Etcher. While it was relatively easy to identify the type of watermarks found in the DMA’s collection, determining their variants and subvariants proved to be more difficult.

Student at a Table by Candlelight has a Pro Patria watermark, which indicates the print is posthumous because Pro Patria watermarks date to the start of the 18th century (Fig. 1). Hinterding does not list Student at a Table by Candlelight on Pro Patria paper, making the DMA’s print the first known impression of this print to be found on this paper.

The Rising of Lazarus: The Larger Plate has a Basilisk watermark. The Rising of Lazarus sometimes appears on Basilisk B.c., but based on the illustrations below, I determined that the DMA’s impression is Basilisk B.d. (Fig. 2, 3, and 4, respectively). This Basilisk likely confirms that this impression is a lifetime print.

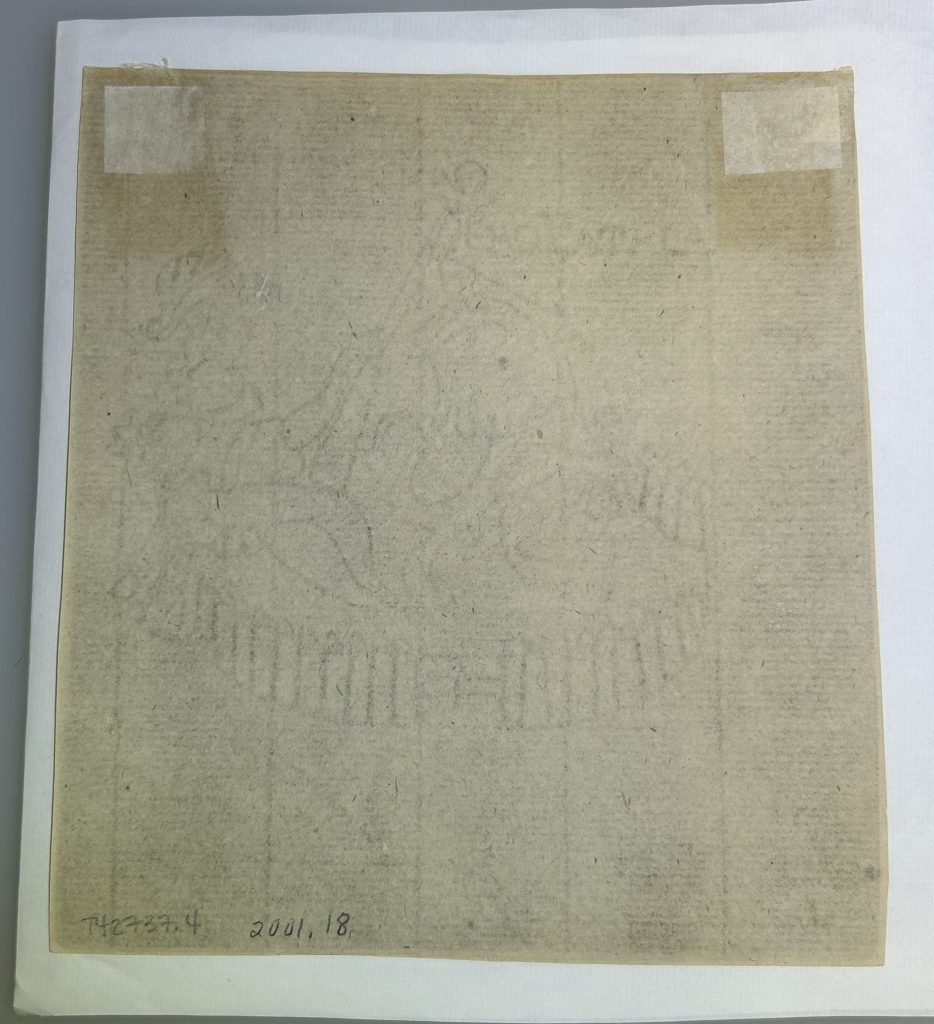

Figure 2

The Rising of Lazarus: The Larger Plate, about 1632. Rembrandt van Rijn. Etching and engraving. Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift, 1990.102. Photo taken and edited by Kevin Huston, 2025.

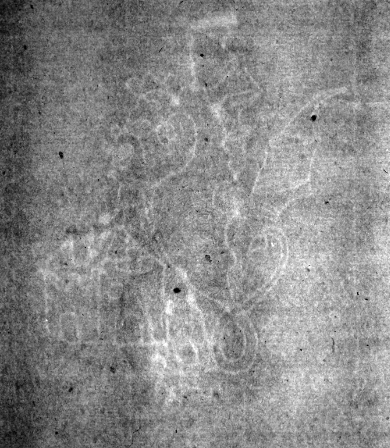

Figure 3

Basilisk B.c. watermark. Image via Watermark Project, Erik Hinterding, Rembrandt as an Etcher, 2006, II, 69.

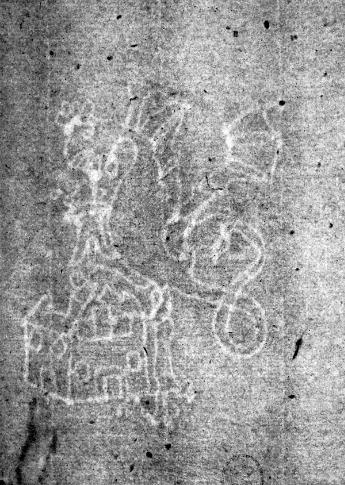

Figure 4

Basilisk B.d. watermark. Image via Watermark Project, Sound and Vision Publishers BV.

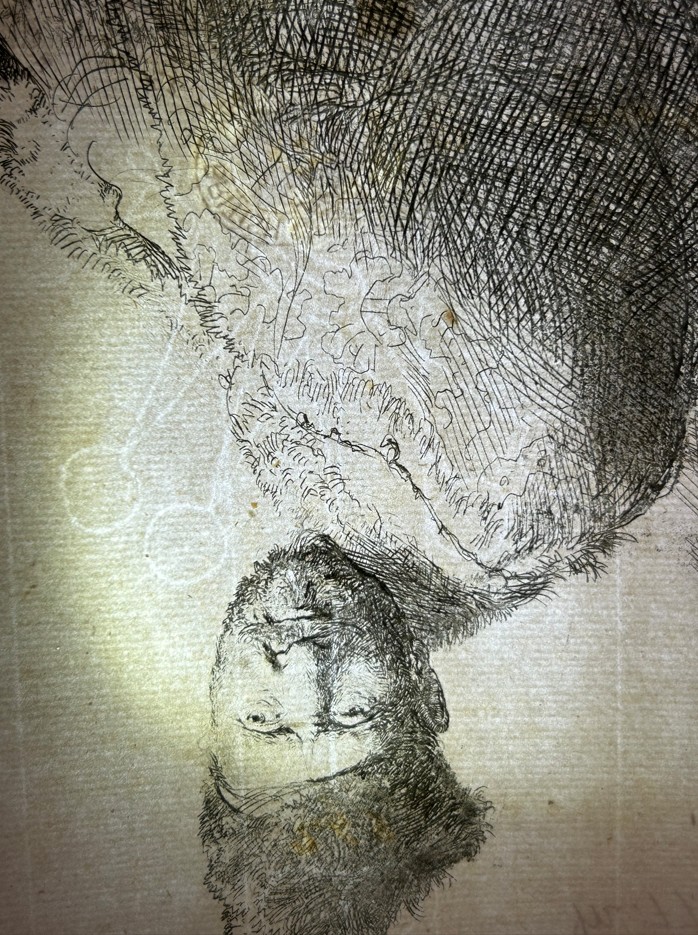

Figure 5 Bearded Man, in a Furred Oriental Cap and Robe, 1631. Rembrandt van Rijn. Etching and engraving. Dallas Museum of Art, bequest of Calvin J. Holmes, 1971.85. Photo taken by Kevin Huston, 2025.

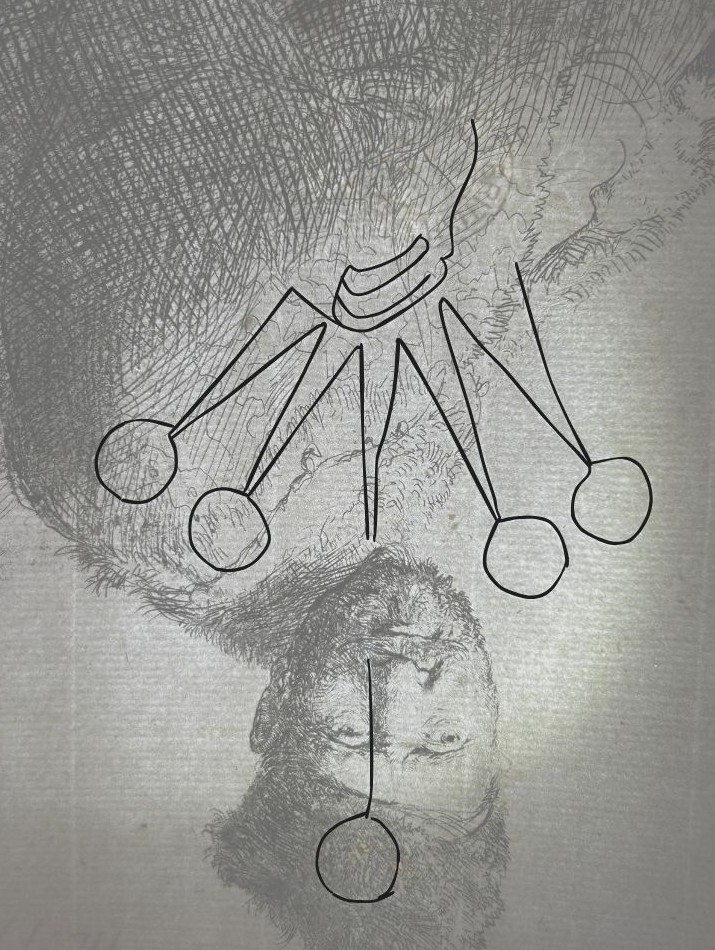

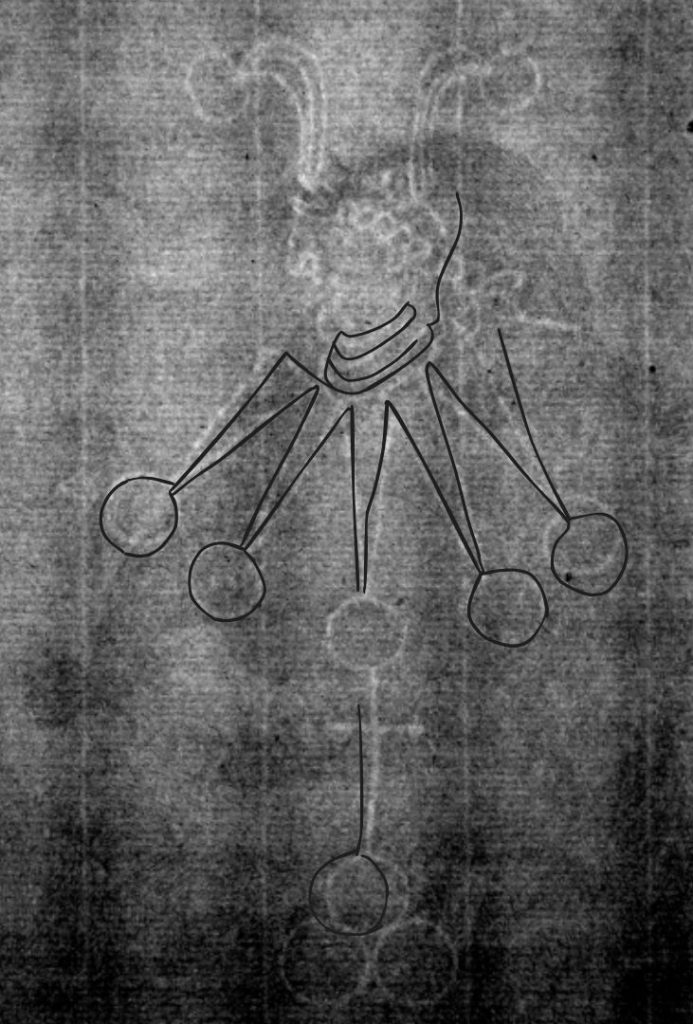

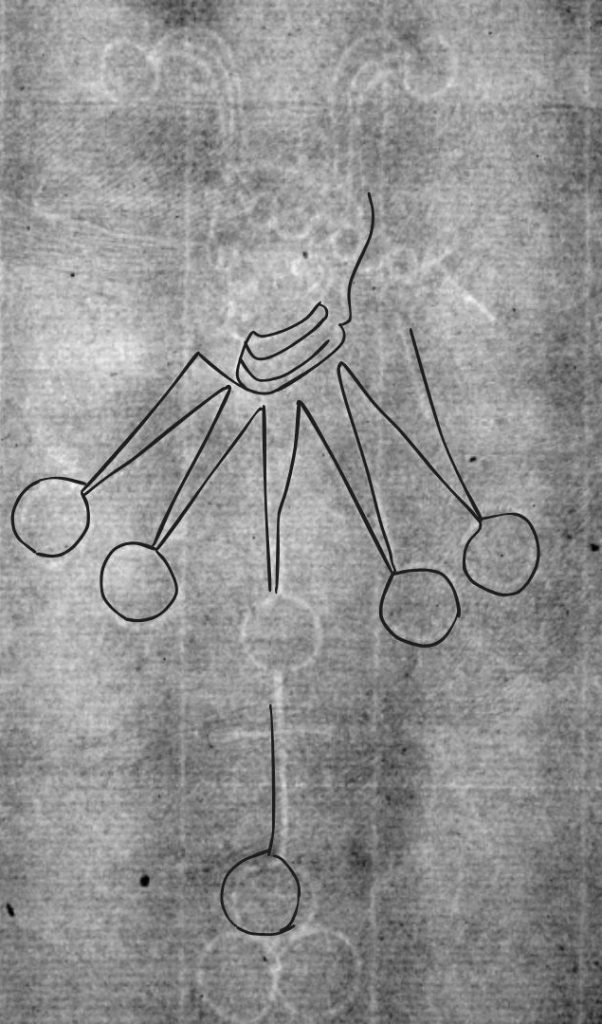

For this last print, Bearded Man, in a Furred Oriental Cap and Robe, I had to get creative (Fig. 5). I knew it was a Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar, but I was stuck between variants K.e.a. and K.f.a. I digitally traced over the DMA’s watermark and overlaid it with examples of K.e.a. and K.f.a. (Fig. 6, 7, and 8, respectively). I determined our print was variant K.f.a. by the crooked middle point. However, since K.e.a. and K.f.a. are so similar, it is possible that they are twinmarks, meaning one design was created for two separate molds.

Bearded Man, in a Furred Oriental Cap and Robe, 1631. Rembrandt van Rijn. Etching and engraving. Dallas Museum of Art, bequest of Calvin J. Holmes, 1971.85. Photo taken and edited digitally by Kevin Huston, 2025.

Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar, K.e.a. Image via Watermark Project, Sound and Vision Publishers BV. Overlaid with digital watermark outline of Bearded Man, in a Furred Oriental Cap and Robe by Kevin Huston, 2025.

Foolscap with Five-Pointed Collar, K.f.a. Image via Watermark Project, Sound and Vision Publishers BV. Overlaid with digital watermark outline of Bearded Man, in a Furred Oriental Cap and Robe by Kevin Huston, 2025.

My time cataloguing these prints has deepened my appreciation for the scholars and curators who dedicate their careers to researching artists such as Rembrandt. I am very grateful for this internship and am looking forward to using my new cataloguing skills in the future.

Kevin Huston was the IFPDA Foundation Summer Intern for Prints and Drawings at the Dallas Museum of Art.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0